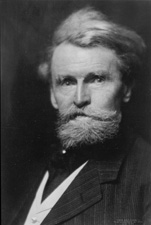

W.A. ClarkTimber brought copper king William Andrew Clark to the Bonner area. In few short years at the turn of the last century, he secured a monopoly on area electricity, and his influence extended from the dam, to the electric company, to the streetcar, to a large saw mill and a flour mill. Despite his stronghold, within seven years of his death in 1925, all these assets had been sold or demolished.

W.A. ClarkTimber brought copper king William Andrew Clark to the Bonner area. In few short years at the turn of the last century, he secured a monopoly on area electricity, and his influence extended from the dam, to the electric company, to the streetcar, to a large saw mill and a flour mill. Despite his stronghold, within seven years of his death in 1925, all these assets had been sold or demolished.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1839, William Andrews Clark was raised in Iowa, where his family homesteaded. After graduating law school, and serving as a Confederate in the Civil War, he worked in the quartz mines in Colorado.

Lured to Montana’s burgeoning mining opportunities in 1863, he first worked in the placer mines before realizing that there was more to be made supplying the miners than in actually mining. He sold supplies ( especially desired items like eggs and tobacco) to Virginia City, transported mail from Helena and undertook banking in Deer Lodge before moving to Butte where in 1872 he bought up a quartz claim and then a foreclosed mill where he began amassing a fortune milling other people’s ore.

Clark’s crafty business sense caused him to anticipate Marcus Daly’s need for water for his new smelter and Daly found that Clark had meantime bought up these rights. Thus began the battle of the copper kings. By 1884 he pushed his way into politics although he did meet resistance when he tried to buy a senate seat in 1899. He was actually elected in 1901-1907.

His checkered career in Montana politics as well as the extent of his copper, banking and railroad empire which made him one of the wealthiest men in America is beyond the scope of the Bonner-Milltown story but makes for lively reading. Clark died in 1925 leaving an estate of $200 million and an impressive art collection now at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington DC. His mansion in Butte is now a bed and breakfast.

In Bonner, Clark created the Western Lumber Company and secured a monopoly on area electricity, and his influence extended from the dam, to the electric company, to the streetcar, to a large saw mill and a flour mill. Clark also created Riverside Park -- a small version of Butte's Columbia Gardens – that opened with great fanfare in 1911. The park was located just west of the dam site and included the dam's reservoir as a recreational lake. On Sundays the street car from Missoula made a special stop at Riverside Park.

Despite his stronghold, within seven years of his death in 1925, all these assets had been sold or demolished.

Anaconda bought the mill from Clark’s heirs in 1928 and continued to operate both mills for several years. The Depression and the difficulty of running two adjacent mills caused Anaconda to close the Western in 1931. It took a couple of years for the mill to be dismantled and the inventory used up. Fifty men were still employed at the Western in 1932, but none in 1933.

2008 saw the removal of Clark’s Milltown Dam. In addition, millions of tons of contaminants--washed downstream from Clark's and Daly's Butte and Anaconda mining operations and collecting behind the dam for over 100 years—continue to be dug out of the Clark Fork River bed. Each night, contaminants are shipped upstream to a repository by train.

All that remains of Clark's Milltown legacy are a couple of dam worker’s garages and the Western Lumber Company office, which is now a restaurant where the safe, still intact, holds pies instead of payroll checks.