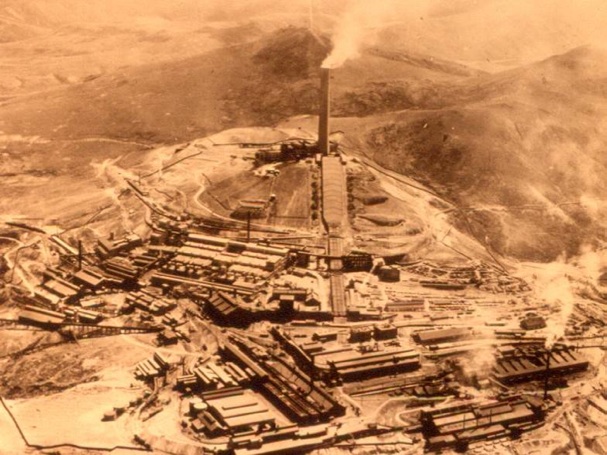

The Hammond or Big Blackfoot Mill

The Hammond or Big Blackfoot Mill

in the mid-1890s. The Montana Improvement Company (MIC) built the first sawmill in Bonner in 1886, but it was largely due to the efforts of partner Andrew Hammond. Initially called the Blackfoot Mill, it was also known as the Bonner or Hammond Mill, not only for Andrew but William Henry Hammond, Andrew’s brother, was general Manager and another brother, George L. Hammond, was in charge of logging operations.

Recognizing the strategic value of the railroad, Hammond and his partners worked hard to attract the almost completed Northern Pacific Railroad (NP) to Missoula, and, with the help of other Missoula businessmen, were successful in getting a major rail center there. The Company was rewarded in 1880s with a lucrative lumber contracts from the NP Railroad.

At Bonner, the mill was built on 160 acres sold to MIC by homesteader Hiram Farr for $100 and “also 2 stoves, chains, broad ax and other tools and implements now on said land too tedious to mention.” Reportedly a cow was added to sweeten the deal. This mill was permanent, not a portable mill that could be moved when the supply of lumber was used up, like the other MIC mills. The Northern Pacific Railroad and its lucrative contracts to MIC, made the permanent location feasible.

The first log went through the mill on June 6, 1886. By August 1886 the mill produced an average of 55,000 board feet of lumber per day. That year MIC purchased an additional half-section of land at the mill site from Northern Pacific for $580. Much of the lumber was shipped to Anaconda and Butte as part of a handsome contract from Marcus Daly, another MIC partner) to provide stulls (supports for mine shafts) for his mines in Butte and fuel for his smelter in Anaconda. The mill also sold a lot of lumber for construction, including the actual building materials for Daly’s smelter in Anaconda. Northern Pacific rails carried the lumber.

A series of corporate name changes for the mill began in 1887. First it was called the Blackfoot Milling Company and by 1888, it was known as the Blackfoot Milling and Manufacturing Company. It seems certain that these changes had to do with the lawsuit brought by the Secretary of Interior against MIC owners regarding timber trespass on the public domain checkerboard lands adjacent to their holdings. The suit dragged on for years resulting in only incidental fines for these lumber barons, who had continued cutting all the while.

When Daly learned that Hammond had not supported him politically in 1889, he turned on Hammond, determined to ruin him. Among other things, Daly cancelled the lucrative Anaconda lumber contract and built his own mill in Hamilton. In spite of this, the Big Blackfoot Milling and Manufacturing Company (yet another name change) continued to expand. It was considered the largest mill between Wisconsin and the West Coast, employing 150 men during the portion of the year that it operated (mills did not run in the winter). It produced 24 million board feet of lumber in 1889, which is equivalent to 5,500 loads on today’s logging trucks. The Anaconda Smelter operated

The Anaconda Smelter operated

from 1902 until 1980. Due to Daly’s constant need for lumber to supply his smelter in Anaconda, by 1898 he decided to buy the mill from Hammond. Hammond, who by then was trying to divest himself of his Missoula assets and move to Oregon, was in a mood to bargain with his rival. The result was the sale of the Big Blackfoot Milling and Manufacturing Company and its timberlands (500 million board feet) to Daly’s Anaconda Copper Mining Company (ACM) on August 15, 1898 for nearly $1.5 million. Interestingly, the mill retained the name of Big Blackfoot Milling Company until 1910, when it became the Anaconda Copper Mining Company, Lumber Department.

Corporate changes occurred here as well. Standard Oil purchased the ACM in 1899, and it became the subsidiary of Amalgamated Copper, albeit with Daly as head. Daly’s death in 1900 brought an end to his involvement. Still by 1915 Anaconda emerged as a company separate from Standard Oil, in control of the world’s copper market as well as Montana’s economy and politics.